I shot a quick video with a really simple overview of how to talk to your customers. Let me know what you think in the comments below.

Uncategorized

London & San Francisco Startup Scenes

Right now I’m flying back to London from San Francisco after a week-long trip with the LDN2SFO group, a collection of entrepreneurs and VCs from London. We toured places like Sequoia Capital, Singluarity University, YCombinator and Pivotal Labs with the purpose of building relationships and strengthening the ties between the London and San Francisco tech startup ecosystems.

I thought it valuable to document my experiences and observations while they’re fresh in my mind. I make no value judgements, simply objective and personal perceptions.

Reinforcement

The first two observations are nothing new and will likely just reinforce what London entrepreneurs already know:

1) London has far less investment activity than San Francisco

Many people make seemingly plausible explanations for why this is, such as the fact that London hasn’t had any runaway successes or IPOs that mint hundreds of millionaires overnight thereby fueling the angel investor community. In addition and for whatever reason, the UK seems to be more risk averse than the US.

Some people have speculated that this risk aversion partly comes from the fact that the UK still attaches a bit of a stigma to a founder that fails, but if this is the case, I haven’t noticed it.

Lastly, the investment process requirements are starkly different. I spoke with several entrepreneurs this week who said they raised up to $150,000 without even showing a pitch deck. One guy said that he raised $1.5 million with 10 slides. The attitude seems as if providing five-year financial projections are laughable and could actually prove detrimental.[1. I’m definitely not advocating for this type of investment behavior as it seems just as noxious as requiring a 100 page business plan. There is a middle ground.]

All of this being said, I do know that the advent of crowd-funded equity solutions such as Seedrs in London are making the process significantly easier. I spoke with one UK-resident who raised a nice pre-seed round in the matter of a couple of weeks by using the Seedrs platform and said the process was painless.

2) London has fewer acquisitions

This is connected with the first point but does play a critical role in the investment market dynamics between the two locations. When we spoke with organizations that work with startups in both London and San Francisco, they mentioned the increase in the number of London-based startups that are placing small teams (usually marketing and/or sales) in San Francisco not merely for the access to the larger market the US provides, but because it increases their visibility to potential acquiring companies.

These two points don’t illuminate anything new as they are already highly discussed among London entrepreneurs.

New Discoveries

While those things were expected, the following subtle points were new to me:

1) Extreme Optimism

By definition, an entrepreneur needs to be optimistic. They need to be able to see what doesn’t already exist and believe that the future can become a reality.

Silicon Valley entrepreneurs however, really take this to the extreme. When presented with a problem, they tried to reason possible solutions as to how they could overcome it. They actively searched for ways that things could be done, regardless of the obstacle.

It’s fair to say that extreme blind optimism is just as bad as extreme pessimism, but it makes for a very different community dynamic. It’s a small difference, but seems to have a cumulative and exponential impact on the ability of that ecosystem to think big.

2) Pay it Forward

This was mentioned by nearly everyone I talked to who had experienced both the Silicon Valley and London startup ecosystems.

Silicon Valley entrepreneurs really want to help those around them. At each event we attended, I noticed that people weren’t just networking with the end-intent of gaining something specific for themselves out of it, but were legitemately interested in helping those around them.

Chris McCann (Startup Digest) put it to me best by saying that a Silicon Valley entrepreneur’s reputation was truly the most important currency available, so it fosters a system of really wanting to help those around you. Once a system like this is put in place, it’s self-perpetuating.

While I’m not saying that there aren’t those individuals in the London startup scene who actively look for ways to help (Here’s looking at you Matthew Stafford), that mindset doesn’t seem to be as prevalent.

Because I think that these two discoveries could potentially prove valuable, I’ve decided to run an experiment. I’ve set up a Meetup group called Startup Karma and I’m going to hold an event later this month with the underlying premise of “Think Big” and “Pay it Forward.” I’m requesting that each individual who attends, shows up with the intent of helping at least one other person. It could be something as simple as providing 20 minutes of specialty-role consulting or making a key introduction.

It’s obviously unenforceable, but I’m hoping that the underlying premise proves beneficial for people and eventually, the ecosystem as a whole.

You can sign up for the group at http://www.meetup.com/StartupKarma/ and I hope to see you there.

Disrupting Financial Technology

I’m working on a new startup that has required me to do a fair bit of research into the financial trading industry. During my market research to see what tools are available, I was astounded at how complex they all were. The vast majority of the software solutions need to be downloaded instead of used in the browser, only a small fraction of those downloads work on anything other than specific versions of Windows, and they are all packed with so many features that I feel like I am trying to pilot a Boeing 747.

As my research continued, my mind kept being pulled back to Clayton Christensen’s work on value-proposition disruption. Nearly every tool’s “unique” selling proposition is something along the lines of “We have more features than the other guys.” In Christensen’s seminal work The Innovator’s Dilemma he shows us that the most disruptive technological innovations aren’t accomplished by providing incremental improvements along existing value propositions lines. (i.e. providing a 1GB hard drive when your competitors are providing 750MB drives) But instead by recognizing that the market is sufficiently satisfied with the capability of products along those lines and re-inventing the value proposition altogether. (i.e. making a hard drive that will fit into a much smaller device)

In the last few years we’ve seen this trend in software from feature-rich to minimalistic simplicity really take hold. [1. Apple helped with the concept of the single-use “app.”] (Evgeny Shadchnev pointed out to me that this is likely a side-effect consequence of that the fact that single-use applications are likely more successful than feature-rich/confusing applications, thus we see more of them.) I remember the first time that I saw Hipmunk and it was obvious that this is the direction that most software should be moving.

So this led me to the question of why this movement to simplicity is almost non-existent in fintech (financial technology)?

I started attending fintech meetups to try and get a better understanding as to why this mindset shift is lagged so acutely in this particular industry – and it became even more confusing. I expected to show up and see a bunch of 50 year old men discussing their portfolios and complaining about how social media is poisoning all of their new recruits, but instead I found a lively group of young professionals who were excited and motivated about the prospects of what fintech could contribute to their future financial careers.

I could see the entrepreneurial spark in the eyes of so many of the them that it only compounded my confusion of the apparent lack of disruptive innovation. These people are intelligent, charismatic, driven and have the means to affect change.

But slowly the answer began to rear its ugly head.

I overheard a very intelligent and energetic gentleman say that he’s been working with a software developer for the last two years writing over 750 thousand lines of code for a solution to a problem that he sees his firm struggling with. After I ask him if he’s pursued a PO (purchase order) or done customer development, he responds with, “Who is going to pay for something that doesn’t exist yet – my product needs to be experienced in order for the value to be understood.”

The next young lady talks about how her consumer-facing solution is going to change the world and after six months of pitching VCs, she feels that she is close to securing funding. [2. There is a great tweet that recently went viral saying, “A founder celebrating raising funding is like a chef celebrating buying the ingredients.”]

More and more of these interactions took place to the point that I now believe: it’s not that there aren’t good fintech ideas out there – it’s that the individuals with the ideas don’t usually have the crossover startup expertise in order to find a profitable business model. Being in finance seems to demand so much of their time that it’s understandably difficult to be an expert in both.

It was this realization that gave me the epiphany to understand how all of these pieces fit together. Being an expert in finance is hard. Being an expert in software development is hard. Being an expert in startup entrepreneurship is hard. (Particularly customer development and the realization that your efforts should be in the search for a profitable business model, not immediately building a product.)

Each of these verticals require such a deep experiential and educational investment, it’s very rare to find a significant-enough overlap to provide the momentum needed to develop a disruptive startup. The personality traits and culture-fits are often diametrically opposed. By this I mean that the exact personality and character traits that would make one most likely to be successful in finance are likely the traits that would make them least likely to build a successfull startup and creatively work with software developers to release disruptive products. [3. This is closely related to the marginal investment lessons taught in most MBA courses.]

The same thing goes for great hackers. The hacker culture is often opposed to the culture of corporate “suits” and big finance – thus further widening the chasm between the two groups. There are very few networking events that would attract the same groups. Some of the greatest “hacks” we’ve seen are because hackers have wanted to build something great for themselves. This explains why there are 1000s of online project management software suites that are beautifully developed and nearly nothing for financial traders. [4. It’s likely that this framework of “being too difficult to find many people who master both” is likely present in other fields as well. (i.e. Medicine, Law, etc.)]

Fintech is ripe for disruption. An elegant pairing of intelligent finance professionals with lean startup and customer development experts that understand the benefit of giving good hackers problems to solve instead of wireframes could have massive results (and profits). As the industry realizes that their premise of “more features is better” isn’t accurate and that bringing powerful financial tools that are easy to use to consumers is far from impossible, we’re going to see increased investment in channeling the masses to the financial markets. I anticipate seeing more founders framing solutions in the fintech space as this industry rebounds, but that leaves a gap of opportunity for those who start exploring the space now.

Thanks to @shadchnev (Evgeny Shadchnev) for reviewing and providing incredible feedback on this essay. Follow me on Twitter @startuprob

Entrepreneur Access to Capital Act

Investing in startup companies is always a risk, but hand-in-hand with this risk comes an opportunity for a substantial reward. Venture capital companies pride themselves on this risk management in order to make money. They loan companies money in return for a fractional ownership, looking to make a handsome profit when the company is sold or goes public with an IPO. The firm that invested in Facebook will likely get a return of 5,000 times on their investment. The issue is that unlike the stock market where anyone can play, only the rich are legally allowed to play this game. We can open up this type of investment to everyone if you assist in supporting the Entrepreneur Access to Capital Act (informally known as the “crowdfunding bill”).

Current Legislation

Under current legislation, startup companies’ funding options are limited to friends and family, established investment firms (i.e. venture capitalists), and accredited investors (i.e. angels). This means that if you want to launch the next great internet sensation and, for one reason or another, you either don’t want, or can’t get, a bank loan, you have to go to one of these sources for funding. Could you tweet out a message to your Twitter followers or post a message on Facebook saying that you’re looking for funding? No. That would be considered illegal “solicitation.” If a friend of a friend hears about your venture and decides that they want to give you some money, can they? It depends on whether or not they’re an accredited investor. With the economy in its current state, we should be doing everything we can to support the flow of necessary capital to entrepreneurs.

The Securities Act of 1933 is the source of our current guidelines for startup investments. First off, it prohibits “general solicitation,” requiring that the startup and the investor have a pre-existing relationship. In addition, it requires that any investors be “accredited,” meaning that they have a net worth of more than one million dollars or two consecutive years of at least $200,000 of annual income.

The purpose behind these restrictions is to protect naive investors. Unfortunately, the legislation is effectively hindering the economy by limiting entrepreneur’s abilities to raise the capital needed to start new businesses. This, in turn, hinders the US economy because we have fewer small businesses creating jobs. And what about those business-savvy individuals with sufficient business knowledge to invest that, for one reason or another, lack the means to qualify as an accredited investor?

We don’t outlaw individuals from going to the casino and risking their life’s savings, why should we outlaw them from taking a risk on a business that could potentially make them a tidy return on investment? If this bill had passed before Mark Zuckerberg built Facebook and you had given him $10,000 of seed money because you thought it was a good idea, that investment would now be worth $50 million. [1. Based on the same terms that Peter Thiel got when he made the first venture capital investment in Facebook.]

Entrepreneur Access to Capital Act

Luckily, Congress has noticed the err in our current legislation and the House of Representatives passed the Entrepreneur Access to Capital Act in November. The House’s bill would raise the restriction of “general solicitation,” thus allowing anyone to broadcast that their startup is seeking funding. You could post on Twitter, Facebook, or even take out an advertisement in the New York Times declaring that your startup was seeking investors. In addition, it would allow anyone to invest in these companies, up to the lesser of $10,000 or 10% of one’s income per year.

The Senate is reconciling two different versions of this bill, one is called the “Brown bill” [2. So named because it was introduced by Senator Scott Brown of Massachusetts.] which has some slight differences to the House bill – the main one being that the maximum investment made would be limited to $1,000. The second bill is the “Merkley bill” and it limits the amount to the greater of $500 or 1-2% of annual income, depending on income level.

If this bill becomes law, it will be a material step forward for our economy and country. Many businesses across the country will get access to the crucial capital they require. Communities will come together to assist one another. Jobs will be created. Fortunes will be produced by scrappy businessmen and women who still believe in that increasingly faint whisper called the American dream.

The Problem

The problem with all of this is that the Senate has been “in chambers” on this bill since December with no action. If you agree with the importance of this bill, I humbly ask you to call your senator and urge them to pass this bill quickly and fairly. (You can find their number HERE) In addition, if you’re so inclined, ask them to reconcile the Senate’s cap-limits a bit closer to the House’s $10,000. Americans don’t need an allowance.

Follow me on Twitter @startuprob.

Identitweet

The Problem

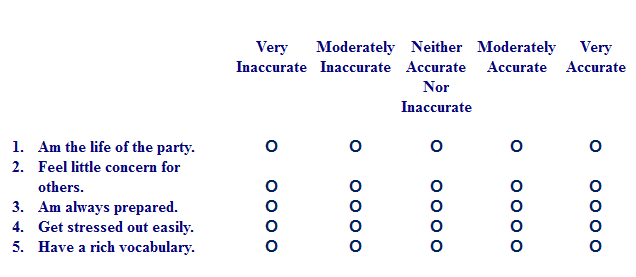

A couple of months ago in my MBA Communications course, I was required to take the Myers-Briggs Type Indicator (MBTI) personality test. It was one of those scantron-looking pamphlets that looks exactly like it did when my parents took it 40 years ago.[1. The MBTI was first published in 1962.] The questions are exactly what one would expect from a personality test, I…

After taking the test, everyone in the class scored their responses and I was surprised at how fascinated everyone was with their results. I admit that I too was quite interested in reading about the intricate details of what this piece of paper thought it knew about me. The professor told us all about the statistical validity of the MBTI and how it’s revolutionized the corporate world – except for one tiny thing: that people tend to answer the questions based on their “ideal selves” instead of who they actually are.

I started to question why in today’s technologically advanced society that we were relying on an individual’s perception of themselves, instead of observing the plethora of actions that are available about them online. With the amount of social media activity and online information available to anyone, I wondered why we couldn’t observe all of that data to make more accurate predictions of personality.

The Experiment

I have a bit of a background in analytics and linguistics and decided I would perform a short experiment. Knowing that Twitter provides an API that gives anyone near-complete access to everything published on its platform, I thought that it would be a perfect instrument of experimentation.[2. I purposely chose Twitter and asked for volunteers because of the openness of the platform. Everyone knows, or should know, that Twitter is 100% transparent and open. (The library of congress records your tweets.)]

That evening I went home and found a non-proprietary open source personality test that wouldn’t require me to pay a fee every time I had someone fill it out. Instead of the four MBTI dichotomies, this previously-proven-to-be-valid test determines one’s big five personality traits: extraversion, agreeableness, conscientiousness, neutoriticism, and openness. Then I used Zoomerang, an online survey-taking tool, to have a sample of people take the test while also volunteering their Twitter handle. Since I was learning Ruby at the time, I wrote some software using the Twitter Ruby framework to slice and dice the different portions of the Twitter API that I thought might be relevant for determining each of these five personality traits.

I imported the results of the sample’s personality tests using binary dummy variables for the indication of whether they were or were not slanted towards that particular personality trait. Since this open source personality test has already been verified as statistically valid, all I needed to do at that point was to find the combinations of coefficients and independent variables that could consistently and reliably predict the correct trait. I imported the results of the software I wrote into the same spreadsheet as the binary personality data to allow my algorithms to use a baseline of zero as a center-point of personality. (So, for example, if the calculation from the extraversion algorithm turned out to be above zero, that person would be an extravert, if it were below zero, they would be an introvert.) With all of this data in hand, I used some statistical software to run multiple-regression tests to see what independent variables, if any, explained a substantive portion of the variance in the any of the dependent variables (the individual traits).

I played around with political affiliation a little but, since I didn’t actually test this with the surveys, it’s purely conjecture. Using a spectrum of generally perceived political biases such as Fox News being more right-leaning and NPR being left-leaning, I proposed to count the mentions and links of each of this networks in the content of an individual’s tweets.

I baselined an integer at zero and decided that for each URL observed from Fox News, the integer would increment by one. For each tweet that included a URL from NPR, it would decrement by one. Finally, if there were a sufficient number of overall links (I didn’t want to be thrown off by a fluke one-off mention), it’s a crude indicator of political affiliation. I’ve considered tweaking this method to only track those media outlets on the edges (far left and right three?) or even using a moving average to weigh those on the media-bias extremes more than in the middle, but I have yet to return to the experiment.

My base conclusions are far from scientific as my sample size was incredibly small. In addition, I had no barrier for “level” of personality trait (0.001 would still be returned as an extravert) so if I were to move forward with this research, I would refine the algorithms and expand the level of sufficiency by requiring the calculation to be, for example, above one or below negative one to display a more confident result. That being said, the crude algorithms do provide some insight into personality through passive observation. (I posted the algorithms at identitweet.com so anybody can view their traits.)

Moving Forward

In addition to personality traits and political affiliation, I believe that the internet provides us a vehicle to determine a great deal of things about people through their actions online. (By “people,” I’m not simply referring to the parochial actions of determining whether someone is an extravert or not – I think we can determine a great deal about society as a whole.)

There’s a lot of potential in this field of study for behavioral investigation. I find myself wondering if it would be possible to monitor individual’s activity in order to predict psychological ailments such as depression or signs of suicide. Could we identify how fitted someone would be for a particular job? Could we serve advertisements to individuals based on their particular way of perceiving information? In terms of society as a whole, could we monitor sentiment (positive vs negative) of tweets that included the word “Obama” made by all people in California versus all people in Alabama to serve as a real-time political polling device? What about brand sentiment? Based by location? And hour of the day?

It’s fascinating to think about what one could determine, purely by knowing where and when to listen.

Follow me on Twitter @startuprob. Thank you to my lovely wife, Stephanie Johnson, for providing valuable feedback on this essay.

April 2012 Update: Due to the increased efficiency developed in the algorithms, the IdentiTweet site’s validity was falling behind so I took it down. I’m currently working on an alternative use for the technology.